CASA TAO . La sombra como espacio de vida.

Algunas casas no se proyectan: se recuerdan. Casa Tao no nació del trazo técnico, sino de la memoria callada de quienes la habitan. Es una casa que no pretende responder a una imagen, sino a una vida. O más bien: a una forma de vivir.

Gustavo creció en una casa humilde hecha más de esfuerzo que de materiales. Hijo de campesinos y comerciantes de artesanías, personas de manos ásperas y mirada generosa, que aunque sus estudios fueron prematuramente interrumpidos, supieron sembrar en él el deseo por comprender el mundo. Creció en Puerto Vallarta, un lugar en la costa del pacifico mexicano, donde el sol y la humedad definen el ritmo de los días y donde la sombra no es un accidente, sino un bien preciado, un verdadero refugio. Desde un inicio, la casa debía traducir esa necesidad de amparo, de recogimiento y de frescura. El concepto de sombra no se entendió aquí únicamente como un fenómeno físico, sino como una condición emocional: una promesa de calma, de respiro, de silenciosa protección frente a un mundo estridente.

Pero la personalidad de Gustavo —tan rica y compleja como el lugar de su infancia— fue lo que marcó profundamente el diseño. Con una curiosidad poco común, es un hombre que ha hecho del conocimiento autodidacta su camino. Filosofía, arquitectura, música, fotografía: me da la impresión que poco le es ajeno. Su biblioteca, con ediciones especiales de Alberto Campo Baeza, Fan ho, Tarkovsky…revela un afecto por la claridad formal, por la geometría esencial, por los patios silenciosos que dialogan con el vacío y con la luz. Conversar con él es sumergirse en una mirada abierta al mundo, profundamente sensible y al mismo tiempo precisa.

Su historia con Cynthia, la segunda habitante, es también parte esencial de esta arquitectura. Junto a sus dos hijas; Mila y Anto, emprendieron su primer viaje fuera del país, a Japón. Aquel viaje, dejó una huella indeleble en su imaginario: la estética del vacío, la limpieza compositiva, la quietud contenida en cada gesto arquitectónico. Nos dijeron entre sonrisas: “Nos gustaría sentir que vivimos dentro de un museo japonés”. Pero no se referían a la solemnidad del museo como institución, sino a ese tipo de espacio que deja que el tiempo se vuelva lento, que la luz se filtre con cuidado, que el silencio se vuelva tangible.

Y así lo intentamos. En un barrio sin grandes vistas, salvo por una plaza arbolada que ofrecía sombra y brisa, decidimos orientar la arquitectura hacia esa frescura. Pero no lo hicimos de manera frontal. Evitamos el uso de grandes superficies vidriadas que pudieran intensificar el calor. En su lugar, planteamos una relación oblicua, sesgada, que permite intuir la presencia de la plaza sin exponerse del todo a la pesada luz del sol. El habitar se enmarca de forma indirecta, como si la casa observara en diagonal, con modestia, apenas dejando pasar el viento y la fragancia que nos envía un no muy lejano mar.

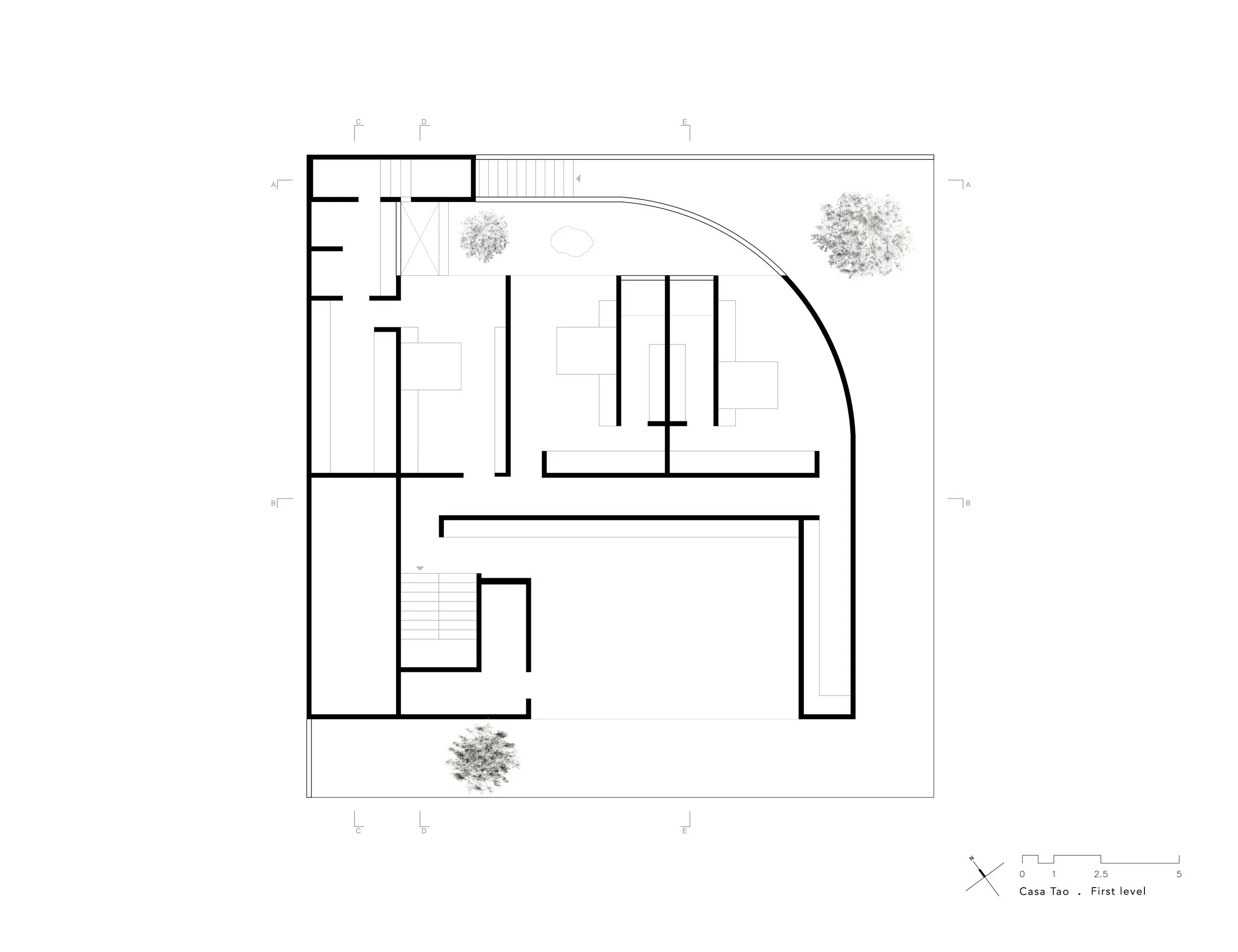

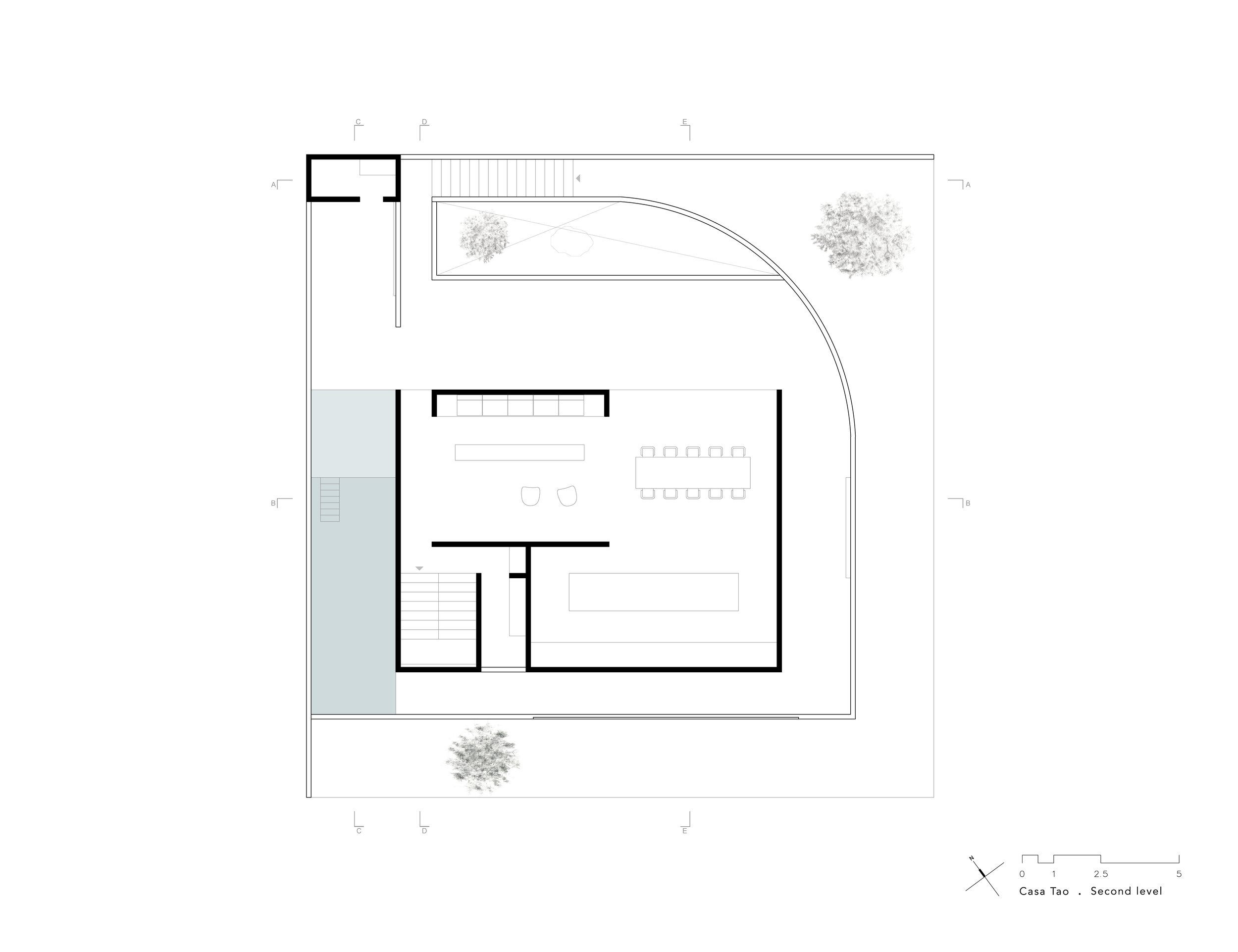

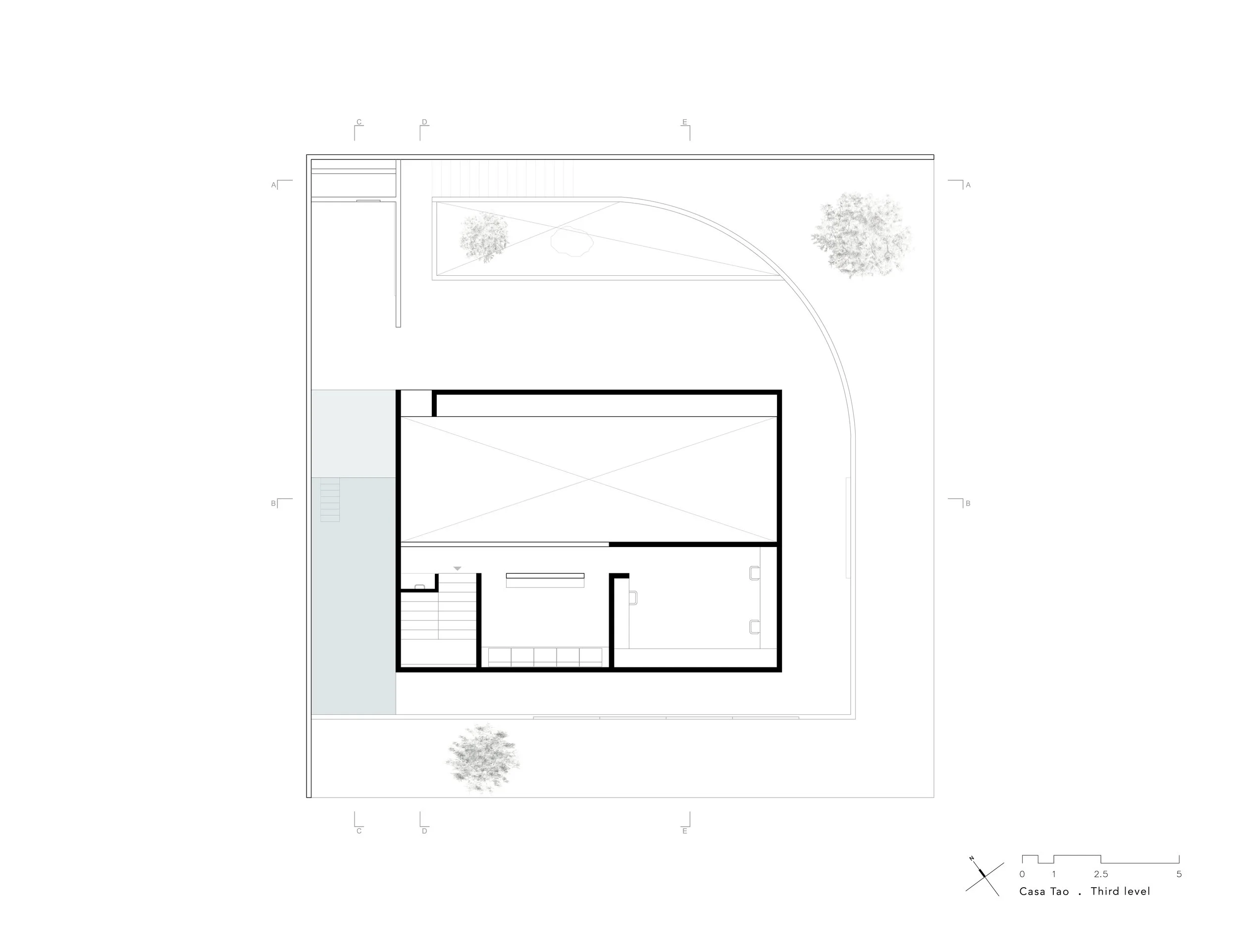

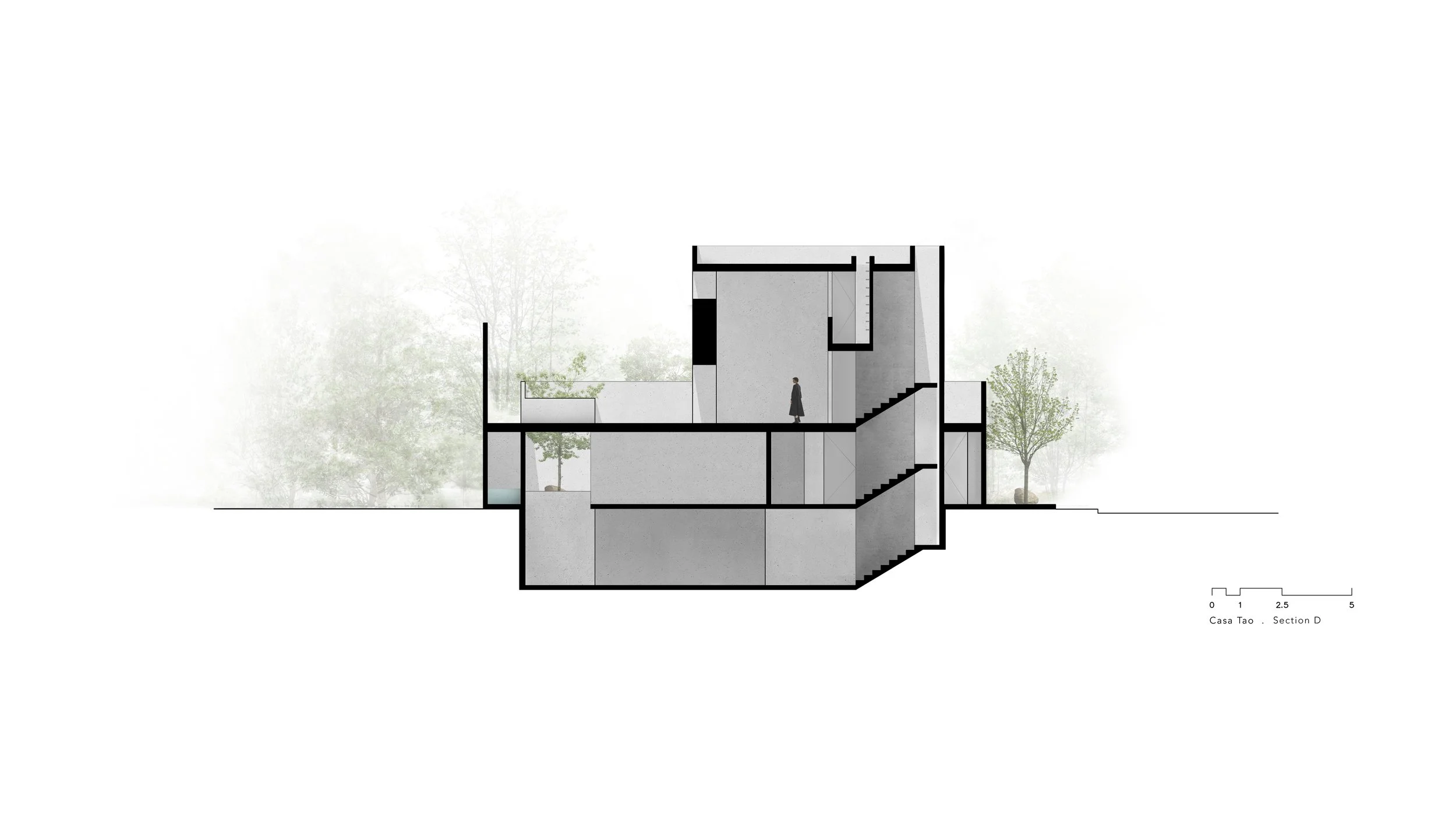

Ubicamos el programa más grande —las habitaciones, garage y servicios— en la base, y sobre él, suspendimos una caja ligera, a doble altura, que contiene las áreas sociales. Esta estrategia nos permitió despegar la vida social del nivel de la calle, rodearla de aire, y abrirla a los árboles y al viento salino que atraviesa la plaza. Los patios elevados actúan como terrazas de contemplación, pequeñas plataformas desde donde se respira mejor la fragancia de las flores y se escucha el murmullo del viento entre las copas de los árboles.

Las habitaciones se organizan en torno a un patio, buscando silencio y aire. Aquí, la intimidad se expresa a través del encierro, no como clausura, sino como mundo interior. Un muro curvo recibe al visitante con suavidad, marcando un umbral acogedor, mientras un árbol te da la bienvenida como si se tratara de un arreglo floral. La casa no mira hacia el vecindario: se voltea, como quien busca el recogimiento. Pero no se encierra: se abre hacia el cielo, la sombra, la plaza. Todo está dispuesto para que el habitar ocurra en una forma más lenta, más plena, más abierta a lo invisible.

La materialidad fue una decisión inevitablemente táctil y sensorial. La blancura encandila bajo el sol costero, mientras que el concreto —pesado, honesto— absorbe la luz con delicadeza. Es un concreto que se vuelve cálido por el uso y por el tiempo. En esta materia la luz no rebota, se posa.

Casa Tao es, en última instancia, una arquitectura nacida del deseo de habitar el mundo con mayor atención. Es una casa que se retira con discreción y ofrece sus espacios como atmósferas para la contemplación y la memoria. En ella, el habitar se vuelve una forma de estudio, de pausa, de gratitud. Cada rincón invita a estar, no a pasar y cada sombra es una promesa de bienestar.

Esta búsqueda deliberada de la sombra, como refugio y como cualidad poética, nos acerca a una comprensión del espacio similar a la que Junichirō Tanizaki describe en El elogio de la sombra. Allí, Tanizaki no celebra la oscuridad como ausencia de luz, sino como un modo más sutil de verla. En su texto, la sombra no es un obstáculo, sino un velo que dignifica; una manera de amplificar la profundidad de las cosas, de permitir que la belleza emerja lentamente, con humildad. Así también esta casa: no se ilumina de forma contundente, sino que permite que la penumbra insinúe, que la luz se filtre sin violencia, que cada espacio sea una experiencia sensorial matizada, contenida, en la que el tiempo se espesa y la vida se aquieta.

-

Casa Tao. Shade as a Space for Life

Some houses are not designed—they are remembered. Casa Tao was not born from a technical drawing, but from the silent memory of those who inhabit it. It is a house that does not seek to respond to an image, but to a life. Or rather: to a way of living.

Gustavo grew up in a humble house made more of effort than of materials. The son of farmers and craft merchants—people with rough hands and generous eyes—who, though their studies were prematurely interrupted, managed to instill in him a desire to understand the world. He grew up in Puerto Vallarta, a place on the Pacific coast of Mexico, where sun and humidity define the rhythm of the days, and where shade is not an accident, but a precious asset—a true refuge. From the beginning, the house needed to translate that need for shelter, for seclusion, for coolness. The concept of shade was not understood here merely as a physical phenomenon, but as an emotional condition: a promise of calm, of breath, of silent protection against a clamorous world.

But it was Gustavo’s personality—as rich and complex as the place of his childhood—that deeply shaped the design. With uncommon curiosity, he is a man who has made self-taught knowledge his path. Philosophy, architecture, music, photography: I get the impression that little is foreign to him. His library, filled with special editions by Alberto Campo Baeza, Fan Ho, Tarkovsky… reveals an affection for formal clarity, for essential geometry, for quiet courtyards that converse with emptiness and light. Speaking with him is to immerse oneself in a view open to the world—deeply sensitive and at the same time precise.

His story with Cynthia, the second inhabitant, is also an essential part of this architecture. Together with their two daughters, Mila and Anto, they took their first trip abroad, to Japan. That journey left an indelible mark on their imagination: the aesthetics of emptiness, compositional cleanliness, the stillness contained in every architectural gesture. They told us with a smile: “We’d like to feel as if we were living inside a Japanese museum.” But they did not mean the solemnity of the museum as institution, but rather that type of space where time slows down, where light filters gently, where silence becomes tangible.

And that is what we tried to do. In a neighborhood with no remarkable views, except for a tree- lined plaza that offered shade and breeze, we decided to orient the architecture toward that freshness. But we did not do so frontally. We avoided large glazed surfaces that might intensify the heat. Instead, we proposed an oblique, angled relationship that allows the presence of the plaza to be sensed without being fully exposed to the heavy sunlight. The act of dwelling is framed indirectly, as if the house were observing at a diagonal, modestly—letting only the wind and the fragrance of the not-so-distant sea pass through.

We placed the larger program—the bedrooms, garage, and service areas—at the base, and above it, we suspended a light, double-height box containing the social areas. This strategy allowed us to raise social life above street level, surround it with air, and open it toward the trees and the salty breeze that crosses the plaza. The elevated patios act as terraces for contemplation—small platforms from which to better breathe the scent of flowers and hear the murmur of wind among the treetops.

The bedrooms are organized around a patio, seeking silence and air. Here, intimacy is expressed through enclosure—not as confinement, but as an interior world. A curved wall receives the visitor gently, marking a welcoming threshold, while a tree greets you like a floral arrangement. The house does not look toward the neighborhood; it turns inward, like someone seeking refuge. But it does not close itself off: it opens to the sky, the shade, the plaza. Everything is arranged so that living happens in a slower, fuller way—more open to the invisible.

The materiality was inevitably tactile and sensory. Whiteness dazzles under the coastal sun, while concrete—heavy, honest—absorbs the light with delicacy. It is a concrete that becomes warm through use and time. In this material, light does not bounce; it settles.

Casa Tao is, ultimately, an architecture born of the desire to inhabit the world with greater attention. It is a house that withdraws discreetly and offers its spaces as atmospheres for contemplation and memory. In it, dwelling becomes a form of study, of pause, of gratitude. Every corner invites one to remain, not to pass through, and every shadow is a promise of well- being.

This deliberate search for shade—as refuge and poetic quality—brings us closer to a spatial understanding similar to that described by Junichirō Tanizaki in In Praise of Shadows. There, Tanizaki does not celebrate darkness as the absence of light, but as a subtler way of seeing. In his text, shadow is not an obstacle, but a veil that ennobles—a way of amplifying the depth of things, of allowing beauty to emerge slowly, with humility. So too with this house: it is not illuminated assertively, but lets the penumbra suggest; it allows light to filter in without violence, and each space becomes a nuanced, contained sensory experience in which time thickens and life grows quiet.

-

道之家

阴影中的生活之所

有些房子并非被设计出来,而是被回忆出来的。道之家并非源于技术图纸,而是源自居住者沉默记忆的积淀。这不是一栋追求形象的房子,而是一种生活方式的投射确切地说,是一种“活”的方式的建构。

古斯塔沃(Gustavo)在一座简朴的房子中长大, 那座房子是以汗水而非建材筑成的。他的父母是农夫和手工艺商人,双手粗糙、眼神温和。尽管他们早早中断了学业,却在他心中播下理解世界的渴望。他成长于墨西哥太平洋海岸的瓦拉塔港(Puerto Vallarta),那里日照炽烈,湿气弥漫,阴影不只是自然现象,更是一种奢侈是真正的庇护。从一开始,这座房子便需回应那种对庇护,内敛与清凉的渴求。在此,阴影不仅是物理现象,更是一种情感状态:一种宁静的承诺,一种对喧嚣世界的柔和抵抗。

然而,古斯塔沃(Gustavo)那复杂而丰富的个性,对本案影响更深。他是一个自学成才,兴趣广泛的人,涉猎哲学,建筑,音乐与摄影。他的藏书中不乏阿尔贝托坎波巴埃萨(Alberto Campo Baeza),范霍(Fan Ho),塔可夫斯基(Tarkovsky)的珍本,这些选择揭示他对形式清晰,几何简洁,静默庭院和光影空白的偏爱。跟他对话,是进入一个既敏感又精准的世界。

他的伴侣辛西娅(Cynthia),以及他们的两个女儿米拉(Mila)和安托(Anto),也是这座建筑的重要组成。他们曾共同赴日本旅行,那次经历在他们的记忆中留下了深刻印象:空灵的美学,简洁的构图,以及每一个建筑动作中所蕴含的沉静。他们笑着说:“我们想住在一个像日本美术馆的地方。”但是他们说的并非严肃的博物馆氛围,而是那种让时间缓慢,让光线细腻渗透,让静默可触的空间。

于是我们努力接近这种愿景。 在一个并无壮丽景致的社区中, 只有一处被树阴覆盖,带有微风的小广场,成了我们愿意亲近的方向。但我们并未以直接方式面对广场,而是采用了倾斜,错位的手法,避免过度阳光曝晒,却又能感知广场的存在。生活的展开是间接的,如同房子以斜视的方式观看世界,仅让海风与花香悄然穿堂而过。

建筑的主要功能体块卧室,车库与服务空间被置于底部,其上悬浮着一座轻盈的双层高箱体,容纳起居与社交空间。这种布局使生命力远离街道层面,沉浸于空气与树影之中,让咸湿的海风从广场穿越而来。上方的庭院变成了观景台,如同小型露台,可以闻到花香,听风吟。

卧室围绕一座内庭组织,追求宁静与通风。在这里,隐私不是封闭,而是内在世界的展开。一道弯墙恩惠地迎接客人,如同温婉的起手式,而庭院中央一株树,如插花般欢迎归人。房子不朝向邻里,而是回转自身,寻求安静;但它并未封闭,而是向天、向阴影、向广场敞开。所有空间皆为缓慢而充盈的生活铺路,开放于不可见之物。

材料的选择源于触觉与感官。白墙在海边强光下刺目,而混凝土沉稳、诚实却温柔吸光,久用之后愈发温润。在这材质中,光线不反射,而是静静停驻。

道之家, 归根结底, 是一种愿望的建筑:渴望更专注地居住世界。它隐退而不张扬,提供静默的氛围,承载记忆与沉思。在这里,居住变成一种学习、一种停顿、一种感恩。每个角落都邀请人“存在”,而非“经过”;每一处阴影都是福祉的暗示。

这种对阴影的追寻,不仅作为避难所,也作为诗意的品质,令我们联想起谷崎润一郎 (Junichiro Tanizaki)在《阴翳礼赞》中的论述。谷崎(Tanizaki)并非赞颂黑暗,而是赋予光之柔和尊严。在他笔下,阴影是帘幕,是深度的象征,是令美缓慢显现的方式。道之家亦然:不以强光照亮,而让

幽微的明暗构成一种丰富的感官体验,让时间沉淀,让生活慢下来。